What does it mean to be a "veteran”?

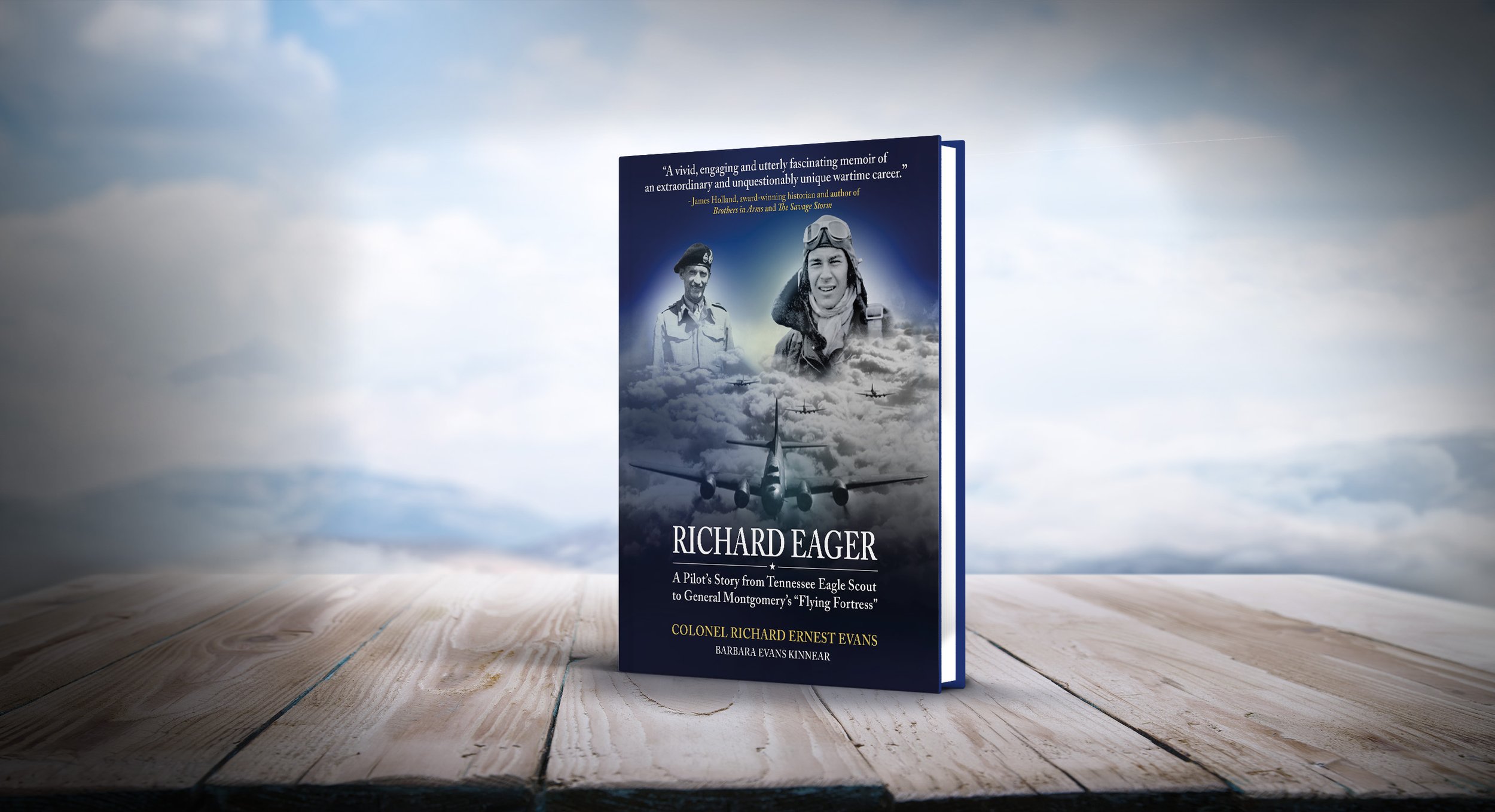

Captain Evans (far right), General Montgomery (far left), and the crew of the Theresa Leta.

In speaking with our “Richard Eager” Facebook community this Veterans Day week, I had an “aha” moment.

One B-17 Flying Fortress aficionado shared with the group what his father once told him, “You could push a screwdriver through the skin of a B-17, but his [plane] always brought him back with several large pieces gone”.

Referencing the many “Swiss cheese” B-17 photos I have seen over the years, I responded rather too lightly that “getting home was the most important part” and what an incredible plane the B-17 was to bring home its crew even under great mechanical duress.

Another community member promptly corrected me: “Dropping bombs on the target was the most important part. After that, you got home or not.”

Indeed, Mr. Frech, you are entirely correct. Duty first, survival second.

How many stories have we heard of successful missions, for which the objective was accomplished but those who facilitated that success never made it home? Air Force history is littered with such records: planes that never returned, planes that never made it to their destination, planes that disappeared entirely. One can only hope that, in the moment those planes were lost, their crews could take some little comfort in knowing they were part of a calling greater than themselves.

This mission-first focus of our servicemen and women is something extraordinary. As a young child growing up on Air Force bases, my mother knew her father took great pride in his work, even with the full knowledge that each day in the air could be his last. As his granddaughter, Colonel Richard Ernest Evans was a legend in my mind. And in my youthful naïveté, I certainly took for granted the miracle of his survival after 54 WWII missions and many years of flying during the Cold War. That is the luxury of being one generation removed from a veteran who lived to share his stories.

When one has a loved one in the military, the focus on he or she returning home safely is an everyday thought, even if it can be pushed to the back of one’s mind with practice. My grandmother spoke about the fear and dread she felt each time her boyfriend— then fiancé, then husband, then father to her daughter—returned to the front during WWII. “You never knew if the letter in your hand might be the last,” she once said.

Returning to the Facebook conversation, I started wondering if those who love and respect our veterans perhaps have a different definition of “veteran” than those who actually are veterans. When I imagine my late grandfather as a veteran, I think of his courage, humility and leadership, character traits I have deduced from family history and his honest and humorous stories. My mother describes him as a loving father and a principled role-model of kindness and determination. My grandmother remembers the young Eagle Scout she fell in love with at the community pool. This is the man, the individual, the veteran.

But when my grandfather, Colonel Evans, reflected on his years in the military, his own desires (besides his love of airplanes) never featured. He most often spoke about the great responsibility he felt to serve and also those he had the privilege of serving with. He wanted to protect home. Our family wanted him to return home.

The balancing act of the veteran is to know that their work, their life, is a part of something larger than themselves. But also the reality that their life, its preciousness, is “the world entire” to those they leave behind and at home.

One loss among hundreds of thousands of war dead or wounded is just a number. One loss to a family and community is everything. There is no reconciling this reality.

This is not to suggest that life is cheap in the minds of those who serve. On the contrary, the prevailing stories of bravery on the front lines highlight the sacrifices of the many to save the few, or even just the one. Perhaps to be a veteran is to value life, respect the fragility of life, more than most. But it is also to recognize that one’s own life is best spent in the service—and sometimes the sacrifice—for others.

These are questions I grapple with this week as our beautiful country celebrates its millions of living veterans and honors the millions more who have already passed on. I take comfort in the fact that no two veterans, or the calling to serve, is alike. Our veterans are human, wholly unique, and so very admired. And I look forward to reading many more stories of service this Veterans Day.

Katie Kinnear

To share the story of those veterans you know and love, please visit our Facebook community.

Barbara (“Bobbie”) Evans Kinnear, daughter of Colonel Richard Ernest Evans, joins historian and author, James Holland, on his podcast, “We Have Ways of Making You Talk”